This article first appeared in The Oxford Scientist, The University of Oxford’s independent science magazine. We have permission from the author, Emma Ford to share it here.

Eunice and Franklin – two names raging across recent headlines as potentially the most severe storms in the UK since 1987. Near record breaking wind speeds of up to 110 mph put many areas on red alert. This meant there was a significant threat to life. Eunice and Franklin, our most unwelcome visitors, can be described as extreme weather events. Weather is the atmospheric conditions of a particular area, defined by variables such as temperature, pressure, humidity and precipitation. In the UK, we have a temperate climate with variable weather. This means we tend to experience cool and rainy winters and warm and rainy summers. The weather in the UK can be variable, as we often see many different weather types within a single day. Extreme weather is different to our normal weather. It is when a weather event is unusual and differs significantly from our expected weather conditions. Extreme weather events in the UK can come in the form of storms, severe flooding and drought. Extreme weather events are problematic, as they have negative socioeconomic and environmental impacts. These can include disruption to daily life and travel, damage to infrastructure and the disruption of delicate ecosystems.

Dealing with our current bouts of extreme weather is trouble enough. However, scientists predict that in the not-so-distant future, due to anthropogenic-driven climate change, some extreme weather types may become more frequent and intense. Anthropogenic-driven climate change is caused by human activities such as burning fossil fuels. This increases the concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas that is notorious for having undesirable residence times of up to 200 years. This means it can remain in the atmosphere for a very long time. While in the atmosphere, it is a highly effective trap for absorbing infrared radiation emitted from the Earth’s surface, creating a warming blanket effect and increasing global temperatures. This has been accelerating since the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s. Humans have been releasing more and more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, tipping the natural balance. It has been calculated by scientists that concentrations have increased by 40% over the past 200 years.

Dealing with our current bouts of extreme weather is trouble enough. However, scientists predict that in the not-so-distant future, due to anthropogenic-driven climate change, some extreme weather types may become more frequent and intense.

But what has this all got to do with extreme weather such as storms Eunice and Franklin? Scientists cannot say climate change is the ultimate cause of singular extreme weather events, although the data do point towards climate change causing more frequent and intense extreme weather. Will storms like Eunice and Franklin become our normal weather? In the last two years alone, there have been a multitude of named extreme weather events which have caused travel delays, property destruction and loss of life. Due to climate change, scientists say we can also expect warmer, wetter winters and hotter, drier summers with more intense rainfall.

Aside from burning fossil fuels, other anthropogenic activities such as how humans have altered the land-surface exacerbate the impacts of extreme weather. Urbanisation and population growth have increased the flood risk of certain areas which when hit by extreme weather events may be more severely impacted. In general, coastal cities will potentially be impacted by climate change more severely, as they are vulnerable to sea level rises from increased temperatures. For example, during Eunice and Franklin, densely populated coastal cities such as Portsmouth were incredibly hard hit with coastal flooding leading to property damage. Unfortunately, this is not an uncommon experience for residents of Portsmouth. In 2018, the storm nicknamed the Beast from the East saw the closure of schools and Storm Deidre destroyed coastal defences as the waves encroached upon the city. The combination of anthropogenic land-use and anthropogenic-driven climate change could make Portsmouth and other coastal cities vulnerable to future climate change and extreme weather.

Other areas of the UK, such as Oxford, have also experienced the effects of extreme weather events. During the winter of 2020/2021, there was severe flooding leading to the closure of much-loved parks and public spaces. Residents of Oxford were seen kayaking across football pitches and meadows, which had temporarily turned to lakes. Many properties across Oxford are also at flood risk, a situation which could intensify in the future due to climate change.

Due to the impacts of these events on society and the environment, it is important to understand changes in the climate and weather, as well as to predict what the future may look like. This is so we can put in place mitigation measures and adapt our infrastructure to extreme weather to avoid severe disruption.

The study of long-term data is key to our understanding of how best to adapt to more extreme weather. Analysis has shown there is no denying that anthropogenic activities since the Industrial Revolution have caused a rise in global temperatures and have changed the climate. Directly linking singular extreme weather events such as Eunice and Franklin to climate change is uncertain. Nonetheless, the data do suggest that the frequency and intensity of some extreme weather events may continue to increase into the future and become more variable. This situation could worsen if we do not work together to decrease carbon dioxide emissions and use our land more sustainably. Scientists know that rising carbon dioxide levels have raised the temperature, which means the atmosphere can hold more water and thus precipitation increases. However, the distribution of this increased precipitation globally and the link to extreme flood events is not fully understood. The key to looking for answers may lie in long-term data analysis.

Directly linking singular extreme weather events such as Eunice and Franklin to climate change is uncertain. Nonetheless, the data do suggest that the frequency and intensity of some extreme weather events may continue to increase into the future and become more variable.

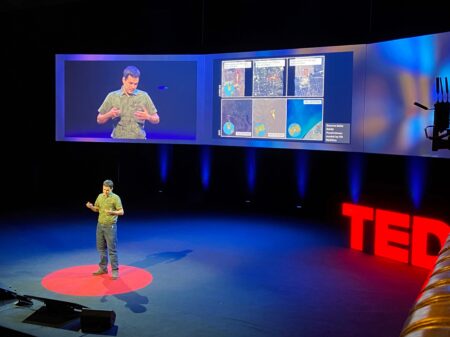

Oxford is home to a unique, long-term dataset. The Radcliffe Meteorological Station in the city centre has daily records of temperature since 1813 and precipitation since 1827. This is an incredible dataset spanning two hundred years and is invaluable to the climate change community as it holds information on weather trends since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. However, this dataset is only for one area of the UK, and the distribution of climate change impacts may vary with location and land-use. There is also UK research focusing on atmospheric circulation patterns, extreme weather events such as flooding and droughts and the consequences for society and the environment. This is important so that we can predict the occurrence of these events and provide policymakers with information for mitigation and adaption strategies.

Our mitigation strategies depend on climatologists’ future projections of changes in weather patterns and climate. The impacts of climate change and the ability to mitigate is often unequally distributed around the globe. Climate injustice is a serious issue. Often the regions around the world that have emitted the least carbon dioxide are suffering the most severe consequences. Whilst residents’ kayak on the flood water in Oxford, peoples’ homes and livelihoods are being destroyed on islands in the Pacific. Furthermore, developing countries may lack the economic support to pay for mitigation and adaption measures.

It is uncertain what exactly the future holds and if extreme weather events and changes to our weather variability becomes normal for us. This depends on how quickly we act to reduce our harmful anthropogenic activities and how the extent of our impacts so far will play out.

Scientists’ climate projections involve different scenarios in the future, depending on different carbon dioxide emission storylines, and a multitude of other anthropogenic factors. Ultimately how we respond to climate change now and how quickly we act to reduce emissions will determine which projection will come to fruition. As the IPCC’s recent statement warned, time is running out and many changes to our Earth may soon become irreversible. It is uncertain what exactly the future holds and if extreme weather events and changes to our weather variability becomes normal for us. This depends on how quickly we act to reduce our harmful anthropogenic activities and how the extent of our impacts so far will play out. The carbon dioxide we have already released into the atmosphere will continue to impact us, but we can stop things worsening. A storyline of Earth’s future climate being simulated today by scientists may become the version of Earth we leave for future generations. We need to act now, before our worst-case projections become their reality.

References

Hartmann, D, L. (2015). Global Physical Climatology (2nd ed). Elsevier: Seattle

IPCC. (2022). IPPC Press Release, Climate Change: a threat to human wellbeing and the health of the planet. Retrieved from: https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg2/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGII_PressRelease-English.pdf

Met Office. (2022). Extreme Weather. Retrieved from: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/learn-about/met-office-for-schools/other-content/other-resources/extreme-weather

Met Office. (2022). What is Climate Change? Retrieved from: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/climate-change/what-is-climate-change

Met Office. (2022). UK Climate. Retrieved from: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/climate/uk-climate

Robinson, M., & Ward, R. (2017). Hydrology Principles and Processes. IWA Publishing: London

School of Geography and the Environment. (2022). Radcliffe Meteorological Station. Retrieved from: https://www.geog.ox.ac.uk/research/climate/rms/

Sharma, A., Wasko, C., & Lettenmaier, D. P. (2018). If precipitation extremes are increasing, why aren’t floods? Water Resources Research, 54(11), 8545-8551. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2018WR023749

Tabari, H. (2020). Climate change impact on flood and extreme precipitation increases with water availability, Scientific Reports, 10, 1-10. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-70816-2