This year marks the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook’s first landing in Australia as part of his epic voyage around the world. But amidst news of his ‘discoveries’, how could the British public distinguish fact from ‘fake news’?

In 1768, His Majesty’s Bark Endeavour sailed from the River Thames round to Plymouth on what was to become one of the most famous voyages in British maritime history. The ship had been loaded with eighteen months’ worth of provisions, for this was to be the first state-sponsored scientific voyage of discovery – a mission that would take her to the little-explored Pacific Ocean and then onwards around the whole world.

Endeavour was on a secret mission to make Britain the most powerful nation on Earth

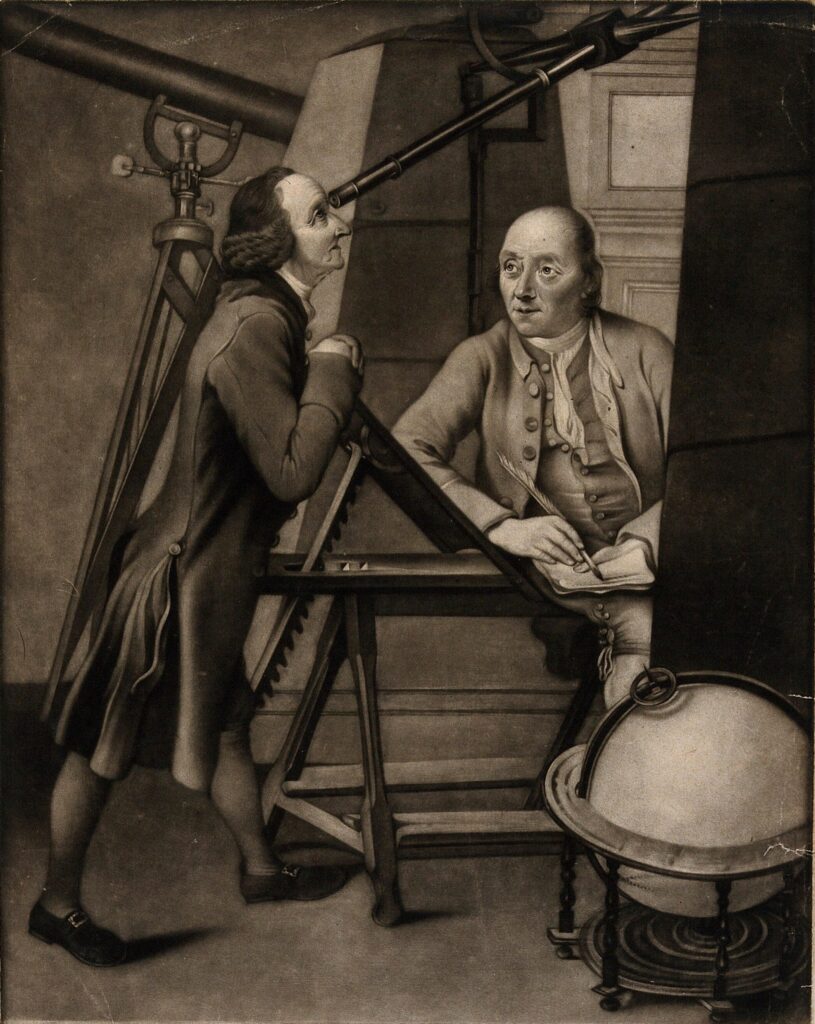

The journey’s purpose was two-fold: to sail to Tahiti – the South Sea island newly discovered by Captain Wallis – to observe a rare astronomical event called the Transit of Venus. This would enable astronomers to work out the distance between the earth and the sun and thus map the heavens more accurately – an essential part of navigation in the days before Harrison’s chronometer.

The second task was to sail to 40°S in search of Terra Australis Incognita -the Great Southern Continent: a land rumoured to exist for over two thousand years. In maritime Europe, the race was on to find it, map it and claim it for the winning nation, along with all the riches it would surely contain. The geographical equivalent of the Holy Grail, many believed the fabled Continent would rival Asia in not only size but also in wealth and political power – and it was for this reason that Endeavour’s instructions were initially kept secret from everyone on board, even the captain, for Endeavour was on a secret mission to make Britain the most powerful nation on Earth.

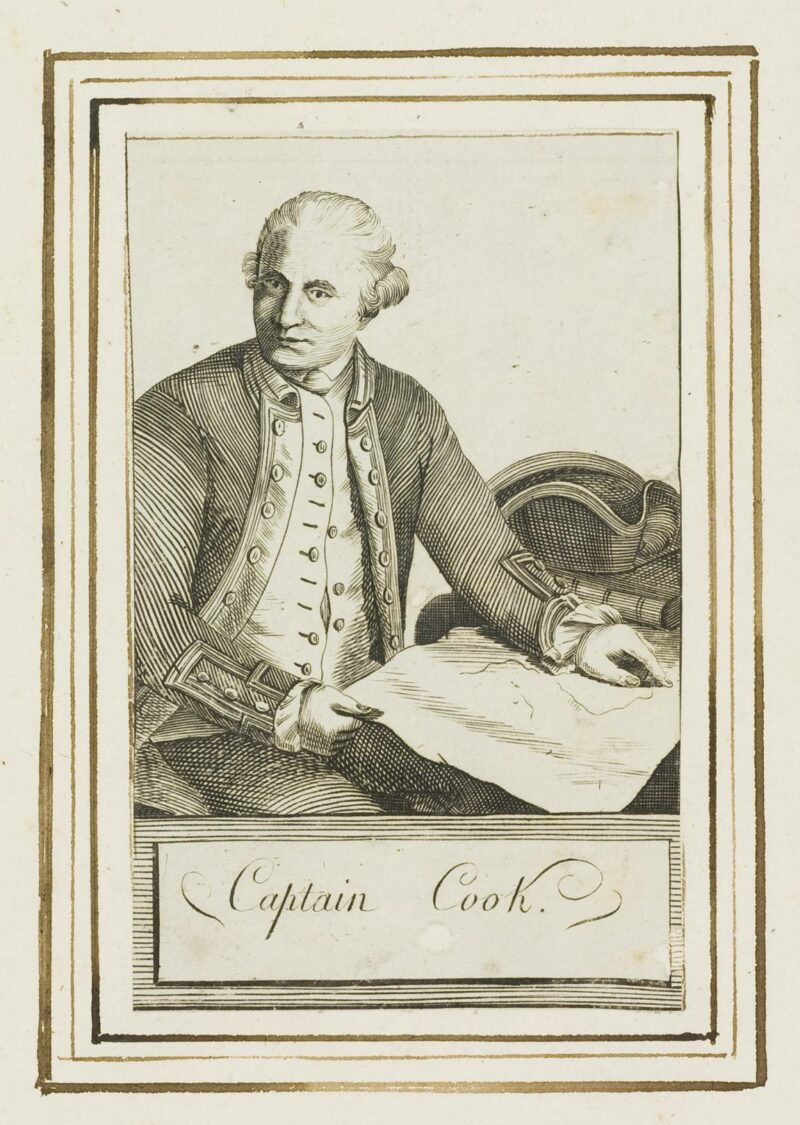

The Government was fully aware of this double agenda. It had part-funded the voyage along with the Royal Society whose purpose was to unlock the secrets of the universe. And their choice of captain for this important voyage? No naval hero or highborn officer but a lowly ship’s master called James Cook.

This choice of a relative nobody might seem surprising, especially in the hierarchical days of the eighteenth century, but the Navy offered a slipstream to those with useful talents. Cook had come to the notice of the Admiralty through his work in North America during and after the Seven Years War. Already skilled in navigation, he had learned the valuable new skills of surveying when fighting the French in Nova Scotia, Canada. These were the early days of scientific cartography: maps would soon become pivotal in controlling an expanding British Empire. Together with his proven interest in astronomical observation, Cook had everything the Admiralty and Royal Society needed and he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant just before Endeavour sailed.

However, in the eyes of the contemporary press and public, he was quite literally anonymous. Newspapers were the ‘new media’ of the eighteenth century, arising from the lapsing of the Licensing Act of 1695 and fuelling and feeding the craze for news that soon became an essential badge of honour in polite society. Periodicals were consumed by the literate and the illiterate; they were studied, shared and discussed to gain social capital in the new culture of curiosity. Much like today’s social media obsessives, news addicts or quidnuncs soon became the subject of public comment, articles and even theatrical plays. However, in 1768, newspapers barely give Cook a mention. Instead, the mission is typically referred to as “Mr. Banks’s voyage” referring to the wealthy aristocrat Joseph Banks who had paid around £10,000 to join the project, bringing with him a retinue of “gentleman philosophers” and artists, and a very real passion for natural history. Little wonder then that the press and public were enthralled by these “Gentlemen of Fortune” on their “Tour of Pleasure”: along with Endeavour herself, they became the celebrities of exotic maritime exploration.

And just like today, celebrity gossip sold newspapers, even if sometimes it was ‘fake news’. In January 1771, while Endeavour was on her way home, the London Evening Post reported that she had indeed “discovered a Southern Continent, in the latitude of the Dutch Spice Islands”. Sadly for Britain, this was not the longed-for Terra Australis but Tahiti where the crew had been observing the Transit of Venus. This time, the ‘fake news’ was not designed to deceive but merely underscored how little the British polite society knew of the Pacific. The public was only just beginning to develop a geographical imagination about the wider world, so Tahiti and the so-called Society Islands were just part of a largely undifferentiated smear of ‘South Seas’ – a fuzzy, generic, exotic conceptual space. It wasn’t the Continent – but it would do: it would sell papers and get people talking.

The Admiralty was not yet ready for a humble farm labourer’s son to be the voice of their new knowledge

Meanwhile, James Cook was about to take his first step towards eighteenth century fame. A month after Endeavour arrived home, he was finally named by the London Evening Post as “Lieut. Cook of the Navy, who sailed round the globe with Dr. Solander and Mr. Banks”! Admittedly, he is positioned as an also-ran to his more esteemed travelling companions but the key comes a little later in the article: the news story then reports how Cook was “introduced to his Majesty at St. James, and presented to his Majesty his journal of the voyage, with some curious maps and charts of different places…; he was presented with a Captain’s Commission”.

This, then, is how to be noticed in the eighteenth century: not by sailing around the world, charting lands previously unknown to the west, but by associating with someone as high status as the king! This gives Cook the validation he needs to start being named in the press as a credible source of new information.

However, the Admiralty was not yet ready for a humble farm labourer’s son to be the voice of their new knowledge. Instead, they reportedly paid journalist John Hawkesworth an incredible £6,000 to write the official account of the Endeavour voyage. Part of a collection of South Sea voyage accounts including those by Byron, Wallis and Carteret, the publishers advertised heavily in the leading newspapers of the day, boasting about the status of everyone involved from Doctor in Law Hawkesworth to the most eminent artists of the day, endorsed by King George III.

This puffery was deliberate and for very sound reasons: in the eighteenth century, the fledgling press was experimenting with new ways of ‘doing’ knowledge. The public – growing in confidence with this new way of making its voice heard – was asking the very same questions we ask today: with so many stories appearing and so much new information, how do you know who to trust and who is just peddling Fake News? The answer, the press found, was by tethering new information to older, already trusted and established sources. Hence the name-checks and references to high-status people, even the King himself.

However, such tethering can be a risky strategy: in 1773, Hawkesworth’s official voyage account went head to head with a rival but unauthorised account drawn from first-hand sources. With each publication vying for popular attention, the ensuing battle for credibility, sales and even moral reputation was played out with pure venom and some 18th century ‘trolling’ in the courts and the press. Rival editors stoked the fire, placing advertisements for the rival accounts side by side. But as the old saying goes, there’s no such thing as bad publicity: while he was sailing the Pacific, Cook’s name and work were now the talk of the town, receiving more mentions than at any other time in his entire career. When he returned from his second voyage in 1775 and learned of the furore – and of the errors in both accounts, Cook used his association with the Admiralty, Royal Society and King to demand successfully that – in future – he would always be allowed to write his own, authentic voyage accounts.

The fact that his second Pacific voyage finally proved that the fabled Great Southern Continent did not exist – and that all those rumoured sightings had been fake news and wishful thinking – barely mattered to the press. Instead of a new Continent, they had a new celebrity – Mai, the Polynesian brought home by Captain Furneaux of Cook’s sister ship, Adventure. Mai was not only real, he took Britain by storm. Feted by the Establishment and press alike, this exotic embodiment of the Noble Savage ‘sold’ more papers than any far-off land.

Within months of Cook’s return, two thousand years of discussion about what lay to the south stopped and the public gaze shifted to north with the dream of a shorter passage to Asia. Meanwhile, Cook’s personal metamorphosis from anonymous captain to cultural icon would only be sealed a few years later by his ‘heroic’ death in Hawaii on his final, fatal voyage – a death that propelled him out of the newspapers and into the national mythology – for, as the contemporary coverage said – here was a man who had given his life for King and country and the dream that Britannia could rule the waves.

Cook’s new status as a cultural icon helped to cohere a new physical and emotional world that was being stretched almost beyond the public’s imagination. And in doing so, the press – that new media of the eighteenth century – helped to forge not only Cook’s eternal fame but a new global British identity.