Tuesday 5th April 2022 marks the 100th anniversary of the death of a woman who was considered by those who have studied her life and work to be among the greatest human beings of all time.

These admirers include a contemporary Indian High Court Judge, M. G. Ranade, and Arundhati Roy who in a recent book, entitled Azadi, asked why no film had been made of her life.

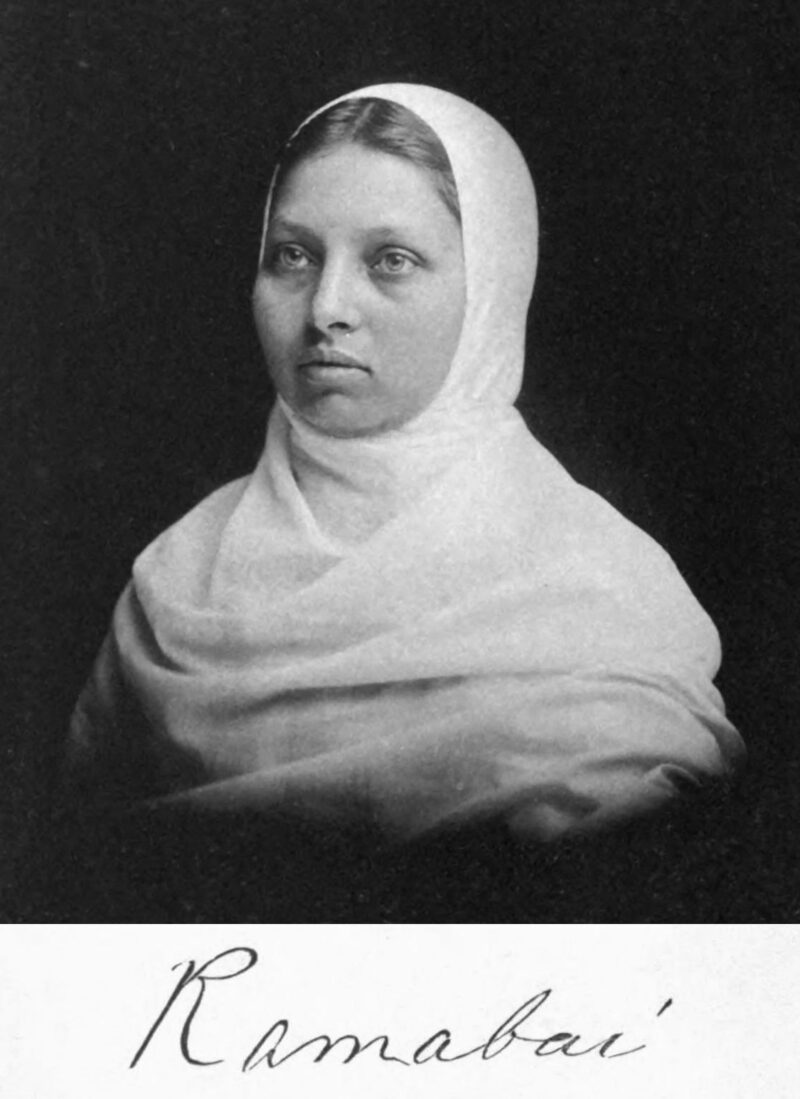

The absence of a film biography is largely due to the fact that the name of Pandita Ramabai (1858-1922) has been all but erased from history, both Indian and Western. So how did someone who read English Language and Literature at Hertford College from 1966 to 1969 come to hear about her? And what part, if any, did Hertford play in the process that led me to devote 25 years of my life to attempt the most comprehensive study to date of her life and work?

There was no hint of a thought about such a project whilst I was at Hertford. I had wanted to read English from the time I first came upon the opening paragraph of Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd in my local library as a ten-year-old on a rainy Saturday morning when our school football match had been called off. This desire had little, if anything to do with India, world history or biography. I had been preparing to apply to Peterhouse at Cambridge when the respective contributions of three members of the Hertford faculty lured me to Oxford. One was Neil Tanner: I was among an early batch of grammar school pupils as part of his radical scheme to make the college more inclusive. The second was Brian Steer, who had attended the same school as me, Leyton County High, and who offered to help Tanner with the search for suitable candidates. (As well as Steer, LCHS produced such distinguished and diverse luminaries as Frank Muir, Derek Jacobi, John Lill and David Cornwell.) The third was “AOJC”, Tony Cockshut. He interviewed me, and to my great surprise, confidently offered me a place.

Once at Hertford with my studies guided by Tony Cockshut, I became aware of at least three seminal influences connecting language, poetry and vernacular Bibles. At this point it should be noted that Ramabai was the first woman to translate the entire Bible from Hebrew and Greek into Marathi, her own language, and to arrange for its printing and publication so that it would be freely available to her fellow countrywomen in Western India. Although his window in the college chapel was installed some years after I had left, William Tyndale became a hero of mine from the moment I realised how much of the 1611 King James Version was derived or borrowed from his pioneering work. Along the way J.R.R. Tolkien and his son Christopher inspired a love of Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse, and from the time I was given a copy of the Jerusalem Bible for which J.R.R. was a consultant, I imagined his influence on the poetry of the Psalms. The translation was faithful to the Hebrew rhythms and form, while fully at home in an English that showed a feeling for Anglo-Saxon rhythms and assonance. (Tyndale had identified this affinity between the two languages early in his work.) My copy of Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Primer, with its selections from the Gospels, has been a life-long companion, and when I recite from it, I always recall the faint whiff of cigarette smoke or nicotine from tutorials with J. F. Kiteley.

In time I produced a complete edition of the Bible in simple English, designed for readers worldwide, particularly those for whom English was a second language, whatever their culture, background, or faith. Whether he said it to all his students I don’t know but AOJC gave me just one piece of advice when writing essays for him: “Use simple words, and short sentences; I find that anything else is an attempt to cover up sloppy thinking.” This Bible would have passed these criteria at least.

It was while working on this major project that I received an invitation to lecture in India in 1997. On arrival, and by complete accident I stumbled into the study of the world’s leading authority on Pandita Ramabai, Professor Meera Kosambi at SNDT, the Women’s University in Mumbai. The incident still feels to me like a discarded episode from Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, in that, however unlikely it seems, it was all to do with the gangrenous big toe of the mother of the person who was due to meet me at the airport and get me to the venue of the lectures near Pune. Meera had just completed a collection of translations of Ramabai’s writings, and kindly offered me copies of all her books and papers on Ramabai. In turn I was able to help her with the cover photo for her forthcoming OUP book. From that moment the question became inescapable: how had someone as distinguished, intelligent, resourceful and radical as Ramabai been eclipsed from history? This proved to be the spur to my study, beginning with a PhD which aimed to identify the reasons for her marginalisation.

On my train journey from Mumbai to Pune, armed with my recently and unexpectedly acquired array of material about Ramabai, I recorded in my diary that the hairs on the back of my neck had stood on end as a single truth dawned. Somehow, inexplicably, my life since discovering Hardy, bore some uncanny resemblances to hers. It’s here that the rubber hits the road. We had both become academics/scholars by less travelled roads: in her case, she never spent a day of her childhood at school or university. We both had a deep love of language and the way languages work, connect and evolve. In her case, Sanskrit was dear to her heart, and she was familiar with the connections between Aryan languages. We both spent time at Oxford. In her case it was most often at the home of Professor Max Müller at 7 Norham Gardens. He was a life-long friend and admirer, and she had a set of his mammoth 50 volume collection of Sacred Books of the East. We had both made whistle-stop tours of the USA: in her case soon after the Civil War; in mine in 1967 with a Hertford friend, at the height of civil rights protests, and not long before the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. We both committed our lives to caring for those needing a safe space and support in residential communities. We were both seized by understanding how people learn: a philosophy of education. We both saw the significance of ideology in power relations. And we were both drawn to Jesus, as followers, but struggled to find a home in existing forms of institutional Christianity.

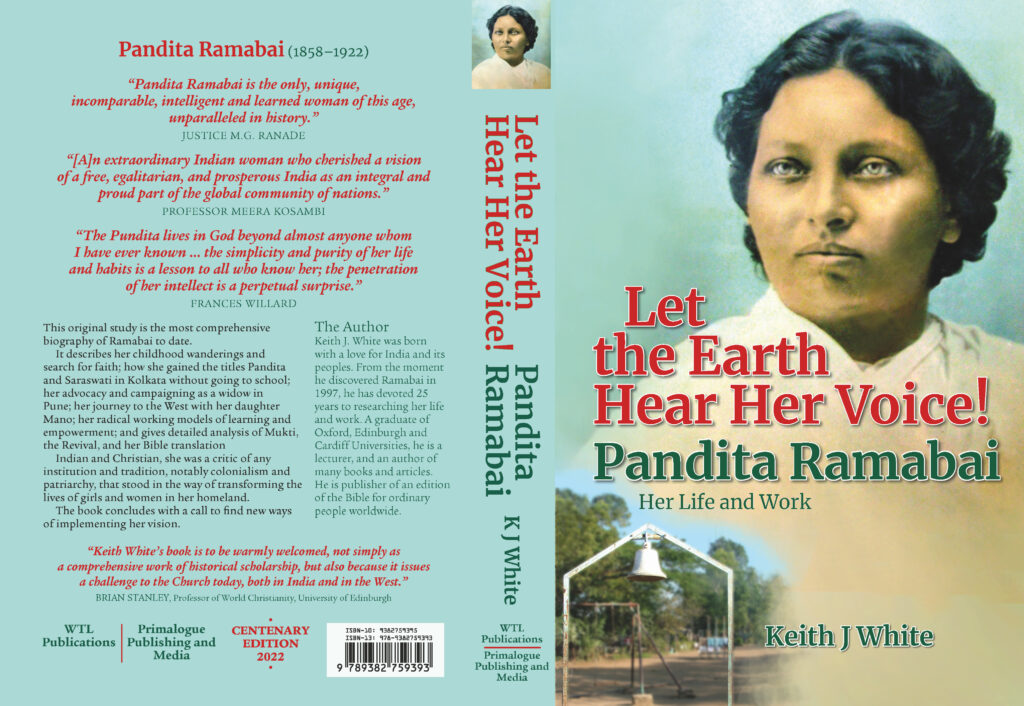

The result of this unfolding catalogue of common experiences and commitments was that I felt I had to write a biography of Ramabai: the only biography I have ever attempted. Like Ramabai’s writings, it does not fit neatly into most forms or genres, and in this I have always been conscious that AOJC’s books were all sui generis. His focus was on the subject, not the critics. The title was never in doubt: “Let the Earth Hear her Voice!”

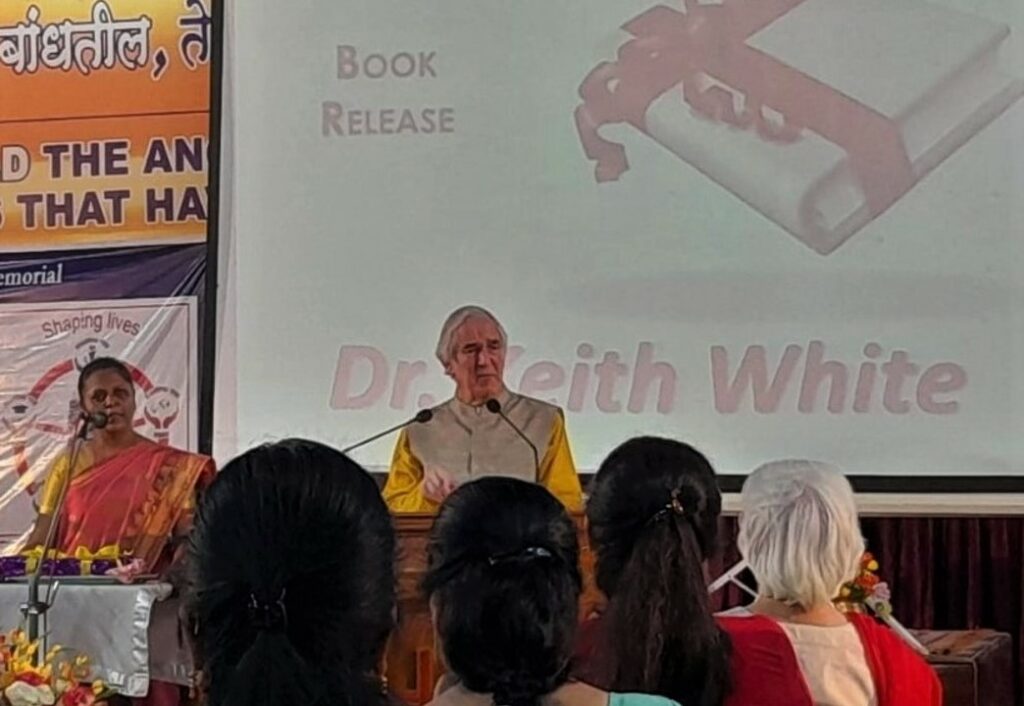

On April 5th 2022, all being well, I will be at Mukti, the community founded by Ramabai near Pune, for a celebration of her life, and the launch of the centenary edition of the biography.

Notes

- ‘Overlooked No More’ is the title of a series of obituaries published in The New York Times. That on Ramabai by Aisha Khan was published in November 14, 2018.

- The Bible (Narrative) NIrV.

- The PhD was completed at Cardiff University in 2003.