For me, there is something utterly compulsive about telling a story in verse. Poets and novelists have been reclaiming poetry’s narrative potential for some time – this genre certainly isn’t new – and now, having written four novels in verse and working on a fifth, I can’t seem to write any other way.

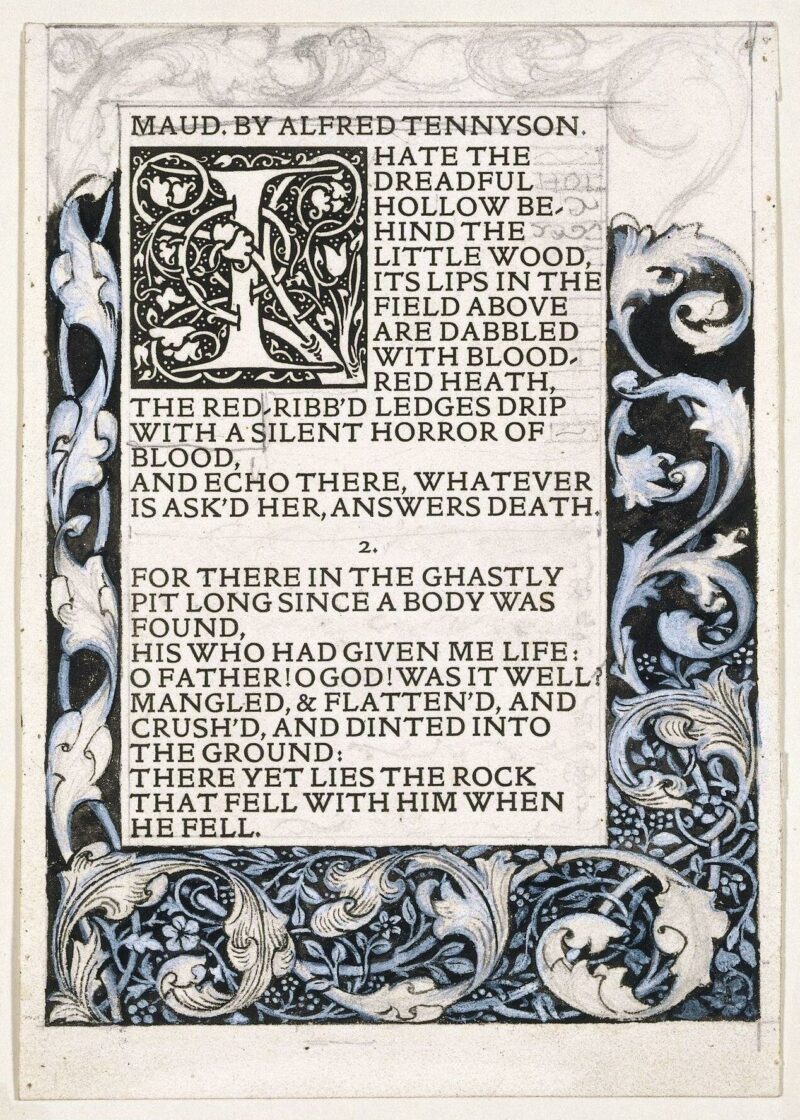

Of course, the free verse form of the modern-day verse novel differs in multiple ways from its forerunners, but the poetic devices and structures that have long been established in our literature remain at the verse novelist’s disposal. Looking back, it was Victorian dramatic monologues that really opened my eyes to the potential of characterisation and story in poetry. I am grateful to have studied Tennyson’s Maud, a Monodrama as a sixth former; my obsession with his embittered and raging narrator and the seductive movements of the poem into varying phases of madness has never left me.

I love the hybridity of this form; that I can feel and hear the text through rhythm and sound, as well as be rapidly seduced by the narrative and voice. Voice is of paramount importance in all writing, but the intimacy of the first person in a verse novel is amplified further by the intensity of the poetry. In addition to this, verse novels can offer the reader both drama and introspection, pace and emotion. I love the rush and chase through a tumbling waterfall of words, or the confrontation with terse short lines, the delight of unexpected wordplay, the punch of a rhyme. And I hope that while the reader is captivated by the story, they might be falling in love with poetry too. I write mostly for young adults and have observed the delight with which they gulp down a novel in verse and feel absolutely satisfied as readers afterwards.

There are some wonderful adult verse titles available (as well as many for young people) if you need convincing of the power of this form. Take the incredible Charlotte by David Foenikos. Inspired by the German Jewish artist Charlotte Salomon, this work is so frighteningly powerful that it feels as if the single end-stopped lines of verse are, as the writer himself says, the only way the reader, and author, can breathe. Anne Carson’s astounding The Beauty of The Husband, is another stark and brilliant book. Manjeet Mann has just won the Costa Children’s Book Award with her novel, The Crossing, a beautiful and necessary story of tolerance and hope told from the dual perspectives of a teenager in Kent and a refugee from Eritrea.

For some young people, it can be difficult to engage with dense prose or the challenge of hundreds of pages. The verse novel can speak directly and from a place of truth about the most important aspects of being human to readers who might not otherwise find books their thing, as well as to those who wish to rediscover their love of poetry and find stories told in new ways. Love, grief, death, heartbreak, loneliness, despair, delight and desire – it’s all there. Nothing is lost. In a verse novel all the raw and awful (in all senses of the word) and beautiful things about being a human are to be found but with the added joy of poetry.

Louisa Reid (English, 1994) has spent most of her life reading. And when she’s not doing that she’s writing stories, or imagining writing them at least. An English teacher, her favourite part of the job is sharing her love of reading and writing with her pupils. Louisa lives with her family in the north-west of England and is proud to call a place near Manchester home. Her debut adult title, The Poet, will be published by Doubleday in June 2022.

Main image credit: Proof of page layout for the front page of Maud by Alfred Lord Tennyson, unused, with hand-drawn border design and woodcut initial by William Morris, printed at the Kelmscott Press; London, 1893. © Victoria & Albert Museum