Renowned Oxford neurophysiologist and Nobel Prize laureate Charles Sherrington once wrote: “The wonderful which comes often is soon taken for granted”. This is a perfect description of what we know as sleep. We are all sleep experts: after all, we sleep every night! However, why do we have to sacrifice a third of our life for this bizarre state of altered, if not absent consciousness, and how we do it in the first place is still a mystery.

Falling asleep can be described by what American philosopher Daniel Dennett called “competence without comprehension“. We are capable of sleeping, but do we actually know how we do it? It was proposed recently that our “default” state of being is not wakefulness, as we like to think, but sleep. In other words, our life is spent primarily asleep, and we only wake up when it is vitally necessary, for ourselves or for the sake of our species.

Others argue that sleep itself has an important function: otherwise why would you sleep at all? It does not seem to be an optional behaviour: we must sleep no matter what, and sleep deprivation has far reaching adverse consequences for our health and well-being. It is as if Mother Nature did not trust our judgement (if we were free to choose whether to sleep or not, who would voluntarily agree to sacrifice a third of one’s life?) and imposed a certain, non-negotiable sleep quota that we are programmed to perform every night. Well, there must be a reason for that! And perhaps what is most striking is how careless most of us are about sleep, and how often we neglect this vital biological necessity for dubious benefits of wakeful activities.

Defining the unknown

Then, what is sleep about? Shall we start with defining what sleep is? We take sleep for granted but it is notoriously difficult to define. Just imagine trying to explain what sleep is to an alien from a planet where sleep does not exist! I would say that, by and large, sleep and wakefulness are defined by the strength of our interaction with the environment. During sleep, we are disconnected from the sensory world outside (although it is important to note that it is easily reversible, unlike coma or anesthesia). On the other hand, during sleep we do not engage in a voluntary movement, and do not act upon the surrounding. Therefore, when we fall asleep, it is not only the world ceases to exist for us, but, figuratively speaking, we also take a leave of absence, and effectively stop existing, from the outer world’s perspective.

Speaking about objective criteria, our traditional definitions of sleep refer to changes in sensory functions, behaviour and brain activity. However, even invertebrate organisms, including those without a well-defined brain, as we know it, such as scorpions, insects, worms, jellyfish or the octopus show sleep-like states! This suggests that sleep does not require the complexity and size of our nervous system, and, importantly, sleep must be essential if most if not all organisms sleep, in some way.

If sleep doesn’t serve an absolutely vital function, it is the biggest mistake evolution ever made

Allan Rechtschaffen

Sleep research is a relatively young field. Only 70 years ago we did not even know that sleep is not of one, but of two kinds. We call the two main sleep stages rapid-eye movement (REM or paradoxical) sleep, and non-rapid-eye movement (NREM or slow-wave sleep). During the night we typically experience 4-5 NREM-REM cycles, each lasting approximately 90 minutes. Traditionally, we talk about sleep and wakefulness as two distinct, fundamentally different states; yet now we know that the boundary between waking and sleep is not that clear. “Fluid boundaries” between wake and sleep, as American neurologists Mark Mahowald and Carlos Schenck put it some time ago, and, according to our current understanding, we are never fully awake or fully asleep! One of the pioneers of sleep research Italian neurophysiologist Giuseppe Moruzzi would use the term dormiveglia, or sleep-wake, to denote mixed states of vigilance. We are more likely to be “half asleep” when we are sleep deprived – all too familiar feeling of being tired, or after we just woke up – the state called sleep inertia, when we feel as being not entirely awake.

Vitus dormivita

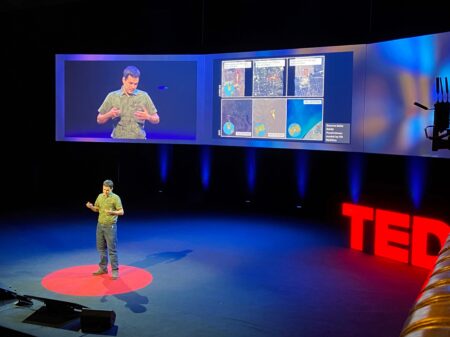

How sleep is controlled by the brain and how it is regulated by intrinsic and extrinsic factors is the main area of research in my laboratory at the Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics. I was fortunate to obtain training in some of the leading laboratories in the field. I did my PhD at the University of Zurich in the laboratory of Irene Tobler – a remarkable mentor, who taught me how to be a scientist and cultivated my interest in studying how different animals sleep, and Alexander Borbély, and that time vice president of the University and the author of one of the most influential theories in sleep research – referred to as the two-process model. According to this model, our sleep-wake cycle is governed by the interaction between our endogenous biological clock and another, still mysterious, homeostatic process, that keep track of our time spent awake and asleep.

Then I spent 7 years in the USA, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, working in the laboratory led by Chiara Cirelli and Giulio Tononi – some of the most creative scientists I ever met, literally bursting with ingenious ideas, and who, to a large extent, defined some of the key research directions in the fields of sleep research and consciousness. I moved to Oxford in 2013, and here I benefit from many collaborations at DPAG and other departments, and especially from my involvement in the Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute (abbreviated as SCNi), which tackles a broad range of fundamental questions addressing the role of the biological clock and sleep for the brain and for the body.

The famous American sleep researcher Allan Rechtschaffen once wrote: “If sleep doesn’t serve an absolutely vital function, it is the biggest mistake evolution ever made.” Alexander Borbély, in turn, remarked that may be we should be asking not why do we sleep, but why it is so difficult to answer this question? We have most advanced methodological tools at our disposal, which we use to address the mechanisms and substrates of sleep. Yet, often all we establish at the end of a most sophisticated experiment is, paraphrasing from Molliere’s “The imaginary invalid”, another “virtus dormitiva”.

New, original ideas about how to study sleep are sorely needed, and now more than ever. Insufficient and disrupted sleep has been linked to a broad range of mental, neurological and physical illnesses, which needs an urgent solution. The current demands – not least those related to the ongoing pandemic and how it affects our lifestyle and working schedules – puts a tremendous pressure on the mental health, and consequences of disrupted sleep may be among the first to take their toll. The stakes are high, and there is no time to lose, but research funding is scarce, and it is now more difficult than ever to retain talented students in academia, given how unpredictable the current climate is.

I must confess, sometimes I feel that I wish for sleep to remain a mystery forever. What can be more rewarding than working on such a fascinating topic? Perhaps I do not need to worry, and it will be enough work for a few generations of sleep researchers. What is more urgent, and equally challenging, is to educate everyone to become mindful of their sleep, learn to cherish it, and do not look at it from above as a loss of time or an inconvenience. It is a precious part of our life – at the individual level and on the global scale. We live on a half-asleep planet. If sleep did not exist, it would have been a different world.