Our archives volunteer Ryan Hamilton writes about Hertford students’ memories of the famous Oxford Union Debate & the outbreak of war in 1939

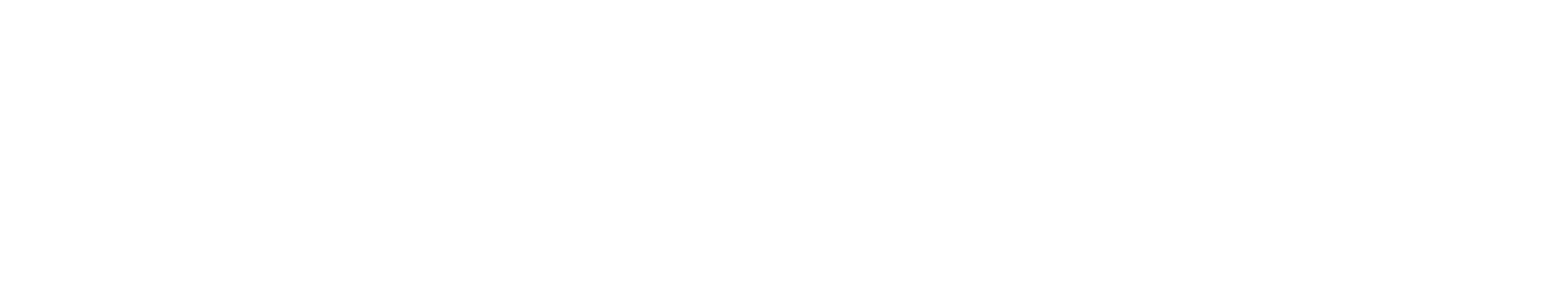

Many of the alumni questionnaire returns in the collection held by the Hertford archives deal with the coming of the Second World War. Written decades later, students poignantly reflected on the coming of fascism and what they either saw or failed to see. Many were pacifists, seeking to prevent a repeat of the devastation of the First World War, but would nevertheless enlist in 1939 in a conflict that would transform life across the world — including at Hertford.

On January 30, 1933, Lincoln student David Lewis was having tea with Adam von Trott, a fellow Rhodes Scholar from Germany, in Magdalen College when a copy of the Evening Telegram arrived announcing Adolf Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor of Germany. Lewis recalled that von Trott “turned as white as the wall behind him and stared at me with desolate eyes.” 11 years later, von Trott would be executed in Berlin for his role in the July 20 plot against Hitler. Today his name is carved on Balliol’s memorial wall along with the students who fell in the Second World War.

But the coming of fascism was not limited to Germany. There was a fascist presence in Oxford in the early thirties — Lincoln student DF Karaka wrote that the fascist organisation, made up of black shirted followers of Oswald Mosley in Oxford, “[shot] up in the twinkling of the eye” in 1933. Karaka described that the Mosleyites stood “for all the possible permutations and combinations of all political creeds, that it is a sort of jamboree in politics.”

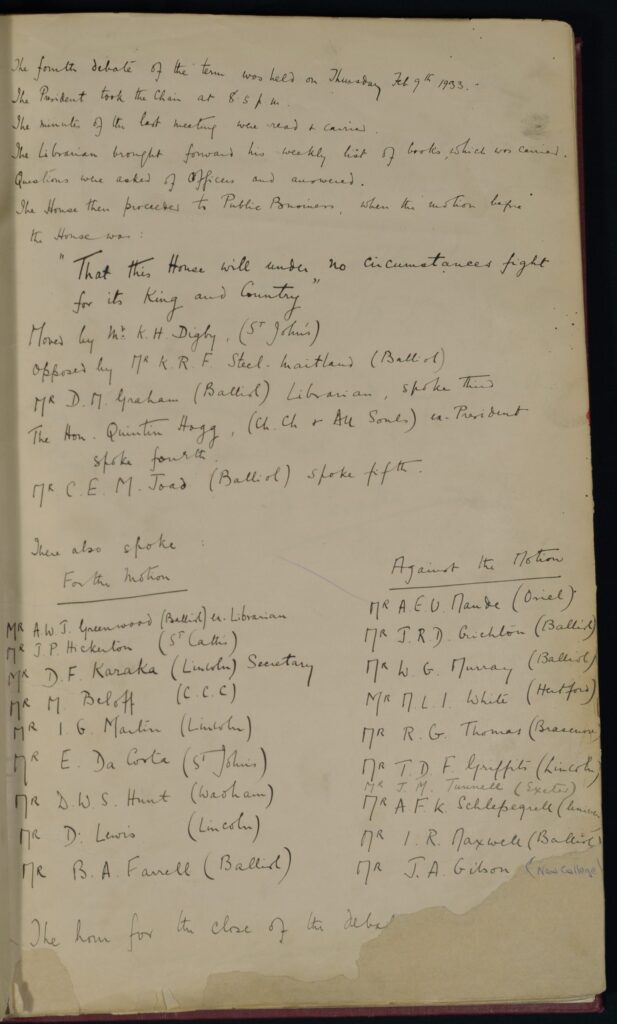

One of the most famous moments in Oxford’s history happened soon after, in February 1933, when the Oxford Union debated the resolution ‘That this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country.’ The resolution carried with 275 votes in favour, and 153 opposed, and soon sparked a national controversy – one that is well documented in the Hertford archives. Gerald Bowser described the King and Country debate as the most memorable event of his undergraduate career:

“The most memorable event (perhaps notorious would be a more appropriate definition) was the Oxford Union debate about not fighting for King & Country. It was entirely unrepresentative of university sentiments and most of us were embarrassed and ashamed. I personally did not even know the debate was taking place and only heard about it afterwards”.

Murray White attended as an “inveterate pacifist”:

“…fully prepared to support the motion, but I was so incensed by the speeches in favour that I actually found myself speaking & voting against. The supporter of the motion were not really interested in peace as such, but spent their time slanging ‘fascism’, ‘militarism’, capitalism’, etc. etc…”

Kenneth Robinson was in the audience but wanted to make clear in his questionnaire that he “voted – but took no other part.”

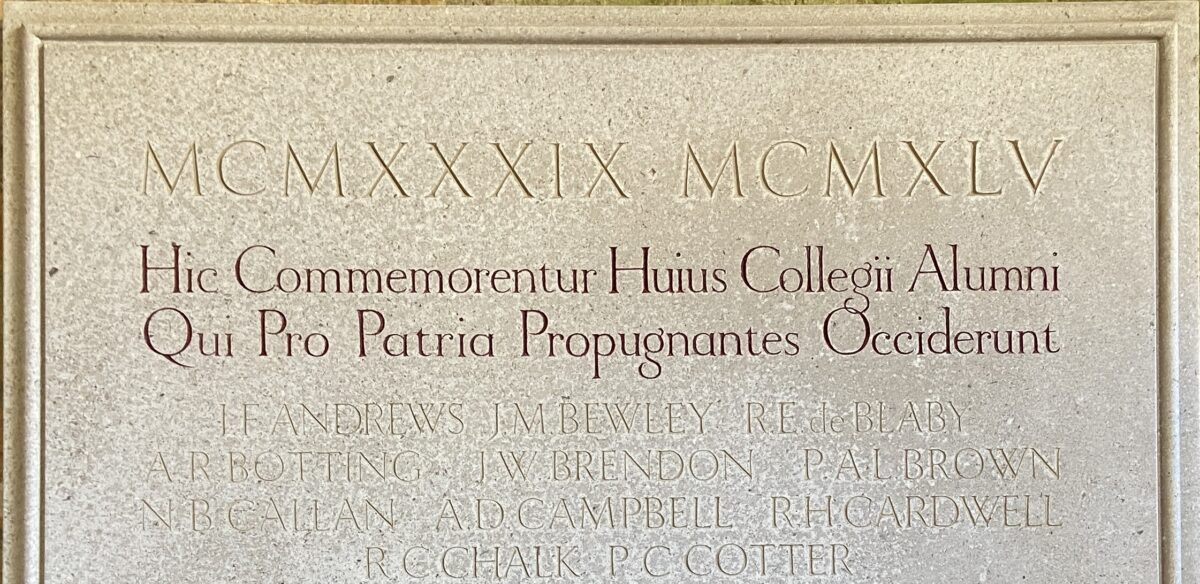

King and CountryDebate.

The result was immediately controversial. Hertford PPE student Bernard Keeling recalled that students rushed into the Union days afterwards to tear out the minutes of that debate. Some blamed an ‘October Club plot’ for the result, but Hertford student Dick Freeman (a founding member of the October Club) refuted that by pointing out both that the Union’s cost meant that few October Club members joined and that the Club had held a meeting of 250 people elsewhere in Oxford that same night. Later, Randolph Churchill returned to Oxford to try and get the result expunged from the Union’s books, but failed. DF Karaka, the Union’s Secretary and a Lincoln student, roomed with Denis Johnson of Hertford. In an account unseen until now, Johnson recalled that Karaka was threatened with debagging for his role in the controversy and was “scared stiff and never left the digs for three days.”

Hertford students dealt with the coming of war in different ways. Some, like Dick Freeman, saw it coming for years — Freeman believed it likely that “the world would be plunged into another war unequalled even by the last” by as early as the summer of 1932, amidst the invasion of China by Japan. But not all were that prescient. Arnold Walmesley remembered that there were no widespread fears of war and Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor had “no discernible effect on College life.” Gerald Bowser travelled in the early 1930s, meeting Nazis in Heidelberg and being in Vienna when local Nazis assassinated Chancellor Dolfuss. Despite being ‘in the eye of the storm,’ as he later described it, the event left “little impression” on him at the time. Llewellyn Lewis, a Hertford student in the early 1930s, remembered that the rise of the Nazis caused “background fears but few, if any, thought there would ever be a war again.” Later in the thirties, J. Brian Liebert was gradually convinced “of the inevitability of war” by Winston Churchill’s speech to the Oxford Union. By 1938, the shadow of the Munich Agreement loomed large over Oxford. John Poole Hughes recorded that Munich “dominated my last year” but he only signed up when war broke out on September 1, 1939. Others, like Derrick Layton, joined the University Officers Training Corps in the months leading up to it.

The war soon changed Oxford dramatically. Following the Dunkirk evacuation, many of the survivors camped in Christ Church Meadow. As the evacuees recovered nearby, many undergraduates faced the reality that their time as a student would soon be over. Herford PPE student Geoffrey Hamber remembered that “the weather was perfect day by day. The news got worse day by day…We all ceased to work, and in my case just played tennis and punted on the Cherwell” as they waited to be called to war.

The number of students in Oxford during the war rapidly decreased as did, according to Brian Galpin, the quality of the food in Hertford’s dining hall. The students were mostly studying ‘short courses’ before they would be called up to fight. Hertford PPE student Frederic Bayliss worked as a fire watcher at All Souls College to supplement his scholarship in spring 1944. He and his colleagues slept in a room overlooking “the High” and were to put out the fire if All Souls was bombed by the Germans, despite the fact they were never told where the water or sand was. Oxford thankfully never bombed but Bayliss recalled “walking round the roof of All Souls on moonlit nights in the black-out was real Oxford magic.” He also recalled an Anglo-Italian student from Romania who was never called up because of “his indeterminate nationality” and, as a result, spent the war in Oxford “free to have a splendid time in the women’s colleges.”

Dom Mintoff, the future Prime Minister of Malta, was also at Hertford during the war, and was an active recruiter for the Labour Club. He was not apparently well liked as he was described as surly, keeping to himself and smoking “a foul-smelling pipe.” John Poole Hughes described him as a “mousey little man, scuttling about the place” and KAB Roberts remembered him being debagged.

Following the victory in 1945, many of the students who had attended on short courses returned to Hertford to complete their degrees – no longer 18 but war veterans in their twenties.

Rationing continued too, ensuring life was harder than the 1930s, especially during what John Nixon dubbed the “great freeze and fuel short[age] of the winter of 1947.” John Coates was reduced to using a lamp and electric fire that winter to achieve even “a modicum of warmth.” Bateson, a scout, woke up student Donald Browne with the comment “Good morning Sir, there’s a foot of snow, your water has frozen in the jug and the chef died in the night so there’s no breakfast.” In an example of the value of the multiple perspectives included in this collection, Miles Malleson also tells the story of Bateson reporting one morning that the floor was slippery due to spilled and frozen water and that the cook had died. But not all students returned. Hamber did not return to Hertford after the war because of what he described as “the death in the war of all my Hertford close-friends of that time.”

All images are of items in Hertford College Archives unless otherwise credited. For more information about this collection, please go to the Featured Collections in our online catalogue. Watch out for further blogs exploring these fascinating memoirs.