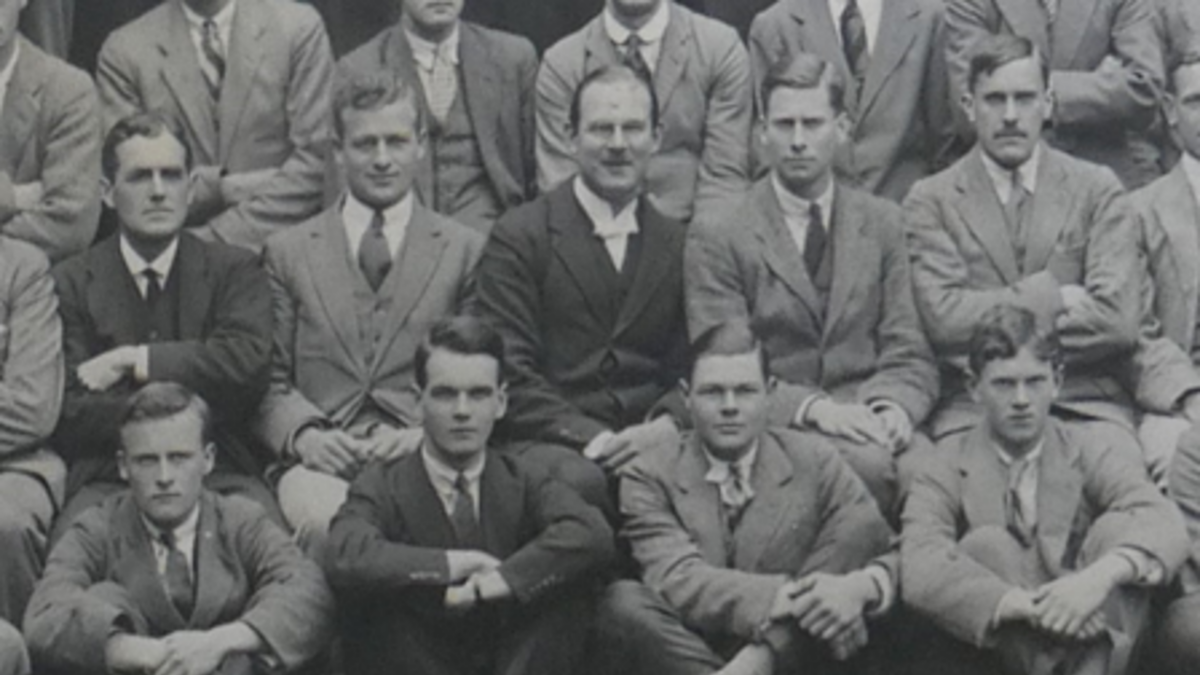

Our archives volunteer Ryan Hamilton writes about student politics as depicted in a set of alumni questionnaires held in the Hertford College archives. In October of Michaelmas term 1931, students gathered at the Oxford Union to await the results of the general election. Prime Minister Ramsay Macdonald had left the Labour Party that summer to […]