Ryan Hamilton, MPhil Student in History at Hertford (2022-2024) writes about undertaking a cataloguing project for the College archive

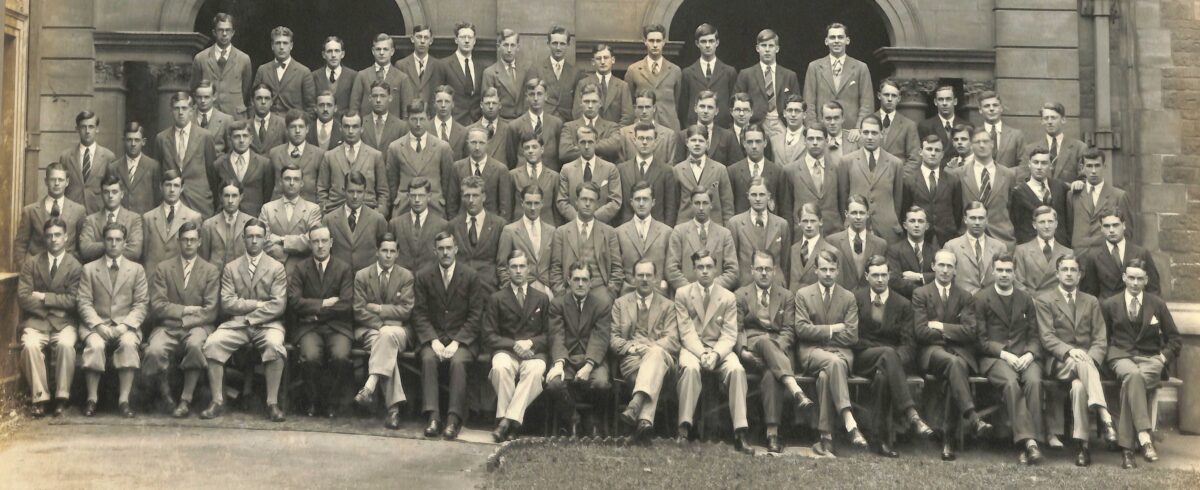

In Trinity term 2024, I began to volunteer in Hertford’s college archive. Lucy Rutherford, the college archivist, suggested a cataloguing project that proved to be a window into another world. In the mid-1980s, the Development Office at Hertford sent their alumni a questionnaire asking about life at Hertford before 1945. They asked a wide range of questions from ‘Why did you choose Hertford?’ and ‘What can you recall of the layout and furnishings of your rooms?’ to asking about the chapel, whether students addressed each other by first name or last and for me, a MPhil student in history, the most interesting question — “What was the most memorable event that occurred during your undergraduate career and what role did you play in it?”

The Development Office wanted to turn these surveys into a piece in the college magazine about student life at Hertford in the 1930s and 40s, but that piece was not written. I suspect it was because the project exceeded their wildest expectations — they received dozens of responses ranging from single pages covered in a handwritten scrawl to 20 meticulously detailed type written pages to, in my favourite case, someone literally copying out and sending their diary from Michaelmas term 1932. The surveys were stored in the library until they were handed over to the archive several years ago, where they remained uncatalogued until now.

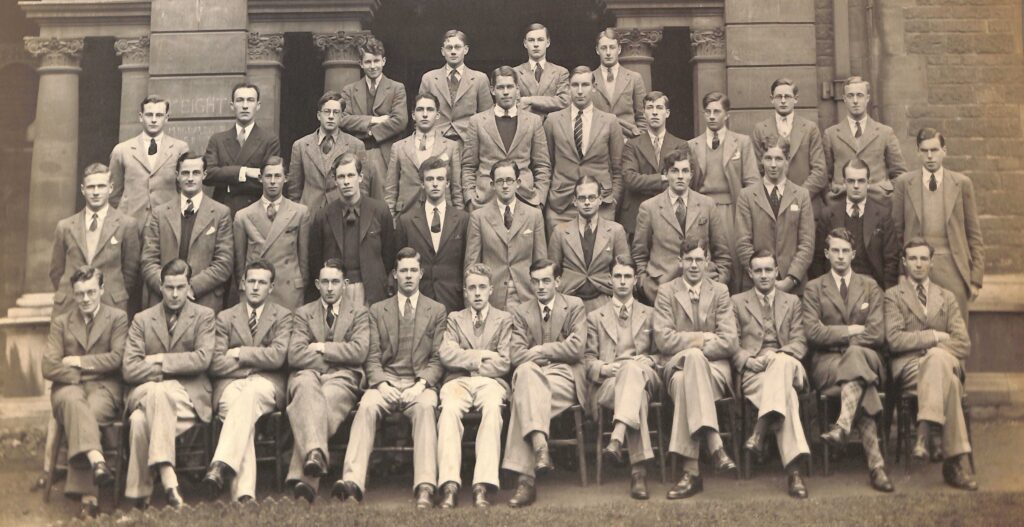

The surveys paint a colourful and vibrant picture of student life at Hertford from the 1920s to the 1940s. The famous ‘King and Country’ debate at the Union is mentioned again and again as the most famous event that happened in their time, and other students vividly describe student Communists or life in wartime Oxford. One of the best things about this collection is the way you see the same story told multiple times from different points of view. Some events, places and ideas show up again and again: Lucy and I laughed at how many of the accounts began with ‘I did not choose Hertford’, and I possess more knowledge of the bathroom situation in Hertford in the thirties than anyone should have (students had to cross the Bridge!) I often found myself flipping back and forth to compare one person’s story to another. Often they aligned and added more detail and sometimes they would contradict – leading me to wonder who was right.

Some of the best accounts in the collection concern the General Strike of 1926. Numerous Hertford students describe lining up at Oxford Town Hall and being driven to Hull to act as strike breakers and work as dockworkers or drive trams amidst the strike. One student, George Waterson, went to Birmingham to work as a special constable. He was given a truncheon and instructed not to use it. Halazy de Chabas, an Hungarian noble, matriculated at Hertford in October 1925. However, as Waterson recalls, he was widely known as ‘Halash de Dabash.’ Tom Boase, a Fellow at Hertford, tried to discourage him from volunteering in the General Strike, as he was not a British subject, but he replied “It does not matter, everywhere I go I hate the lower classes!” There are numerous characters like this who appear over and over again in these stories. Akatani Genichi, a Japanese student known as George Akatani, was well liked and described as “universally popular.” Nevertheless, according to John Poole Hughes, he “openly warned us that the Japanese would wipe us all out.” He returned to Japan in 1939 and joined the Japanese foreign ministry in 1945 – there is no record of what he did in between. He translated for the Japanese Prime Minister in a summit with President Nixon in 1969 and ultimately had a high ranking role with the UN.

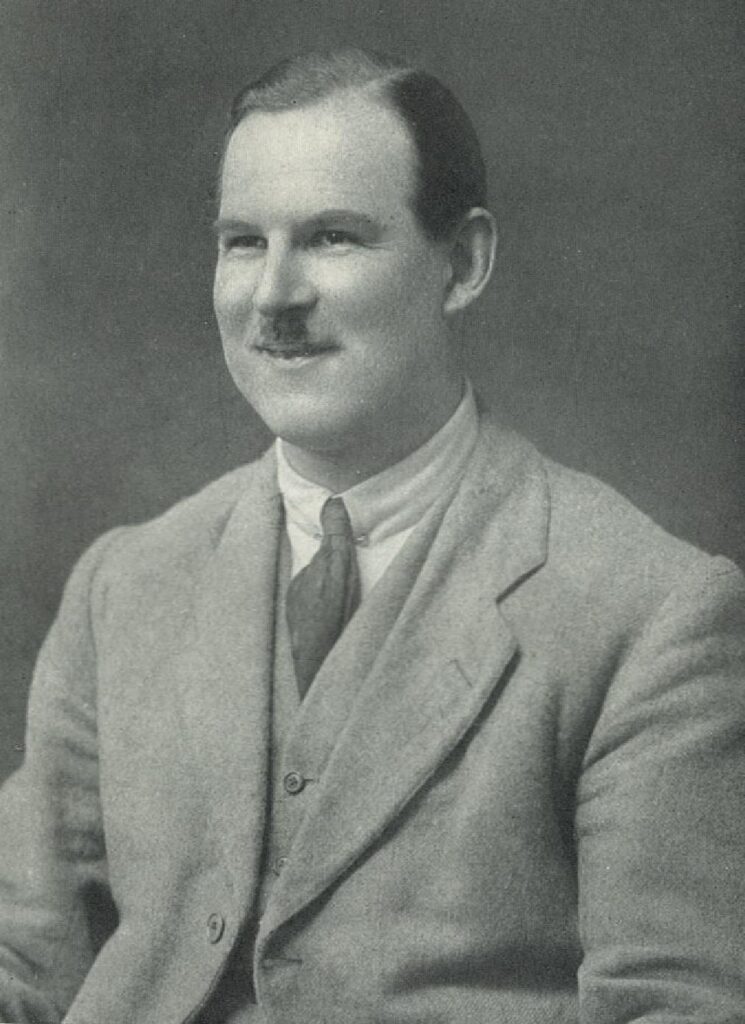

CRMF Cruttwell, a long-time staple of Hertford who served as Principal in the 1930s, also makes frequent appearances in these memoirs. He is almost always described as a “character”. Cruttwell’s misogyny was legendary, and he banned women from attending his lectures – though Gerald Bowser, a student of Cruttwell’s at Hertford, wanted it recorded that he only pretended to be a misogynist. Cruttwell was known as “fearsome” and intense, but nevertheless generally well-liked. He hosted students at his cottage during vacations. One student called him “quite approachable” and another called him “extremely kind” but he could behave strangely at times and walked with a limp. James Phelips remembered in his own survey that they all attributed this behaviour to his service in the First World War.

One other figure who makes repeated appearances is Cruttwell’s great nemesis: the novelist Evelyn Waugh, author of the great Oxford novel Brideshead Revisited. Waugh generally hated his time at Hertford and the feeling that seems to have been mostly reciprocated — Waugh’s classmate Waterson described him as “commiting his own peculiar brand of academic suicide.” Waugh hated Cruttwell, his history tutor, so much that he gave numerous villains in his books the name Cruttwell. Waugh made little impression on Waterson besides wearing “very light-blue tweed plus four” that they all found “outlandish.” Bateson, a scout, described Waugh to Robin Miller as a “man of gloomy mein”. In Brideshead Revisited, the character Sebastian Flyte soon “appeared at [Charles Ryder’s] window…with unfocused eyes and then, leaning forward well into the room, he was sick.” Postlethwaite, Waugh’s former scout, later confirmed to Donald Browne, who lived in Waugh’s former ground floor rooms twenty years later, that this had actually happened to Waugh. John Flynn, a classmate at both Lancing and Hertford, simply wrote that “my recollections of [Waugh] are not suitable for the archive.”

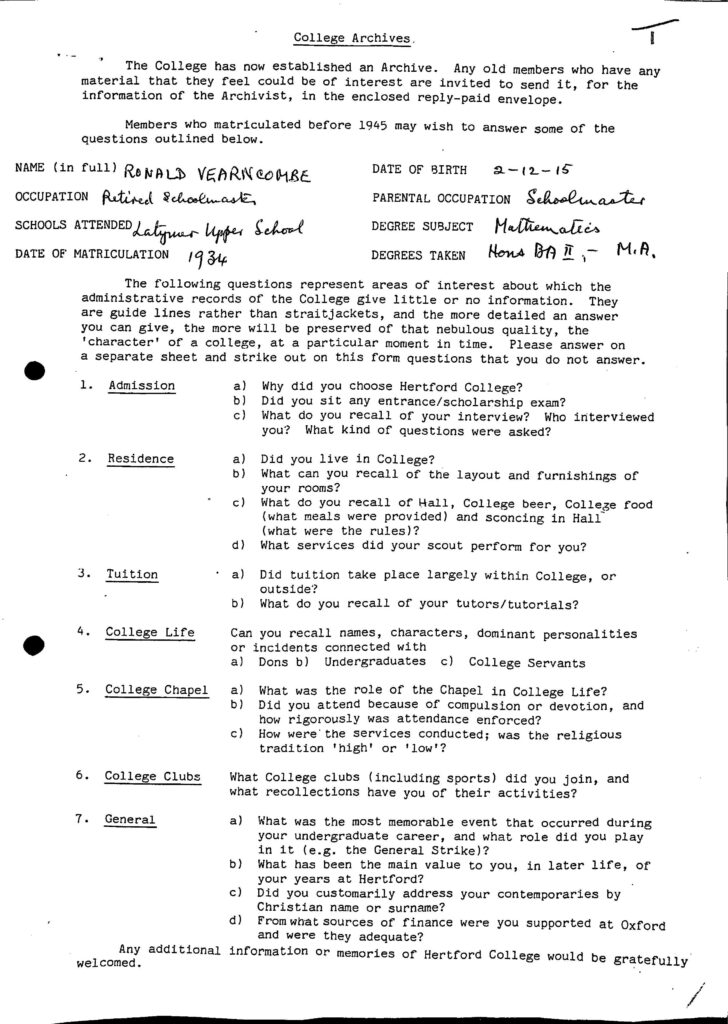

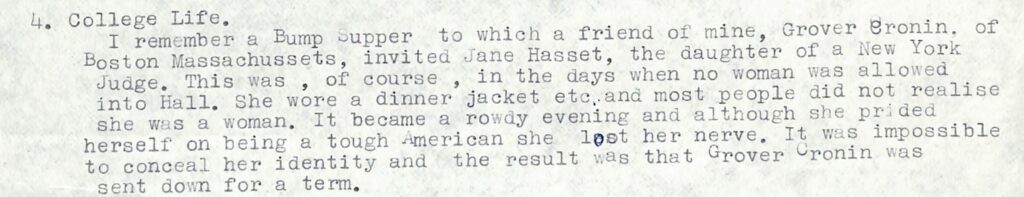

One of the most famous events that took place at Hertford in the 1930s occurred during the Bump Day Supper of 1937. Grover Cronin, an American student from Boston, was dating a fellow American at one of the women’s colleges, the daughter of a judge from New York. She was named either Jane Hasset or Joan Watt – depending on who is telling the story. Bill Atkinson, the JCR President and President of the Boat Club, recalled that Cronin had been unable to see his girlfriend due to the last two weeks of rowing training before Summer Eights and Atkinson then insisted that Cronin not skip the Bump Day Supper. Accordingly, Cronin and his friends hatched a plan. She cut her hair, wore a suit, they made sure she was surrounded by Cronin’s friends (KAB Roberts walked behind her to disguise her “wobbly female bum”) and they snuck her into hall, passing her off as the St. Peter’s cox.

Hertford in 1937 was an all-male college and even mentioning a woman’s name at dinner would lead to a sconcing – having to drink 2 ½ pints in one go. Needless to say, her presence was a major breach of the rules. However, it seems to have gone smoothly and Cronin’s friends thought they had gotten away with it, though one remembered that she “lost her nerve” despite being a “tough American.”

Several days later, the girlfriend’s landlady discovered the man’s suit in her room. The girlfriend, “to clear her reputation” as Atkinson phrased it, clarified that a man had not been in her room, she had worn it herself to the formal dinner. The landlady promptly called Dean Felix Markham, though some accounts suggest it was Bursar WLF Ferrar. Atkinson remembered that Markham had sat very close but not recognized her. Perhaps more plausibly, organ scholar Robin Miller wrote that Markham told Cronin that he had realized she was a woman but decided to let it slide as it was “a good lark”. However, now that he had been told by the landlady “he had to do something” and poor Grover Cronin was soon rusticated for a term. This story shows up again and again in the alumni memoirs. It seems like just about every student at Hertford in 1937 remembered it — it must have been the talk of a very different Hertford than the one we know now.

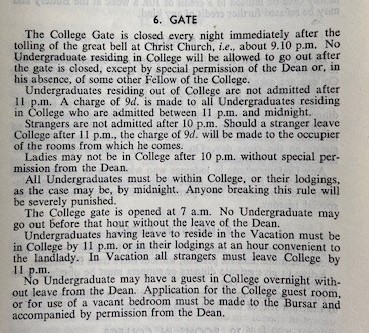

There are other differences too. Student life was tightly regulated by the college in a way that is starkly different from now. Graham Phipps remembered that the front gates closed just after 9 PM, when Great Tom tolled, and all visitors, especially women, had to be out of the college by then. Students could return until 11, after which they were required to pay a fine of 9d. Students who tried to re-enter after midnight needed either a “special arrangement with the porter” or to sneak in through a window at New College Lane. As someone who has come and gone through those gates after midnight, I can confirm that these restrictions are long gone.

Yet, in many other ways, accounts of Hertford felt strikingly familiar. Allan Kerr lived in the Octagon in the late 1920s, a room above the JCR where I spent a great deal of time as it is now the Middle Common Room for graduate students. Kenneth Robinson also lived in the Octagon and wrote about its “wonderful view of the Sheldonian” – the view is as wonderful today. Kerr also remembered that, due to the small size of the college library, he worked at the Codrington Library at All Souls – I wrote much of my dissertation at All Souls due to the ongoing library renovations. Much has changed, but much has stayed the same.

My job as a volunteer was to catalogue these documents – this consisted of first reading through the collection to understand what it looked like and then filling out a detailed spreadsheet where I provided biographical information on the writer, recording their name, matriculation date and subject, and summarised what they wrote, writing this summary in a way that would be useful to researchers. I also identified the most interesting ones which could be digitised and made available through the online archive catalogue. This work was incredibly enjoyable, but it was time consuming and requires knowledge and training — but now these records are accessible to any student or researcher who wants to see them. This is the value of supporting college archives. The archives and library at Hertford are a wonderful place and it was my pleasure to be a small part of their team for a few months!

All images are of items in Hertford College Archives. For more information about this collection, please go to the Featured Collections in our online catalogue. Watch out for further blogs exploring these fascinating memoirs.