Our archives volunteer Ryan Hamilton writes about student politics as depicted in a set of alumni questionnaires held in the Hertford College archives.

In October of Michaelmas term 1931, students gathered at the Oxford Union to await the results of the general election. Prime Minister Ramsay Macdonald had left the Labour Party that summer to form a National Government with the Conservatives to implement cuts to unemployment benefits amidst the Great Depression. As the night dragged on, the scale of the National Government’s victory, and Labour’s landslide defeat, became clear. Ultimately, the National Government won 554 seats and Labour just 46. Murray White, a Hertford student at the Union that night, remembered that his ‘lefty friends’ were all stupefied as the ‘results came in on ticker tape.’

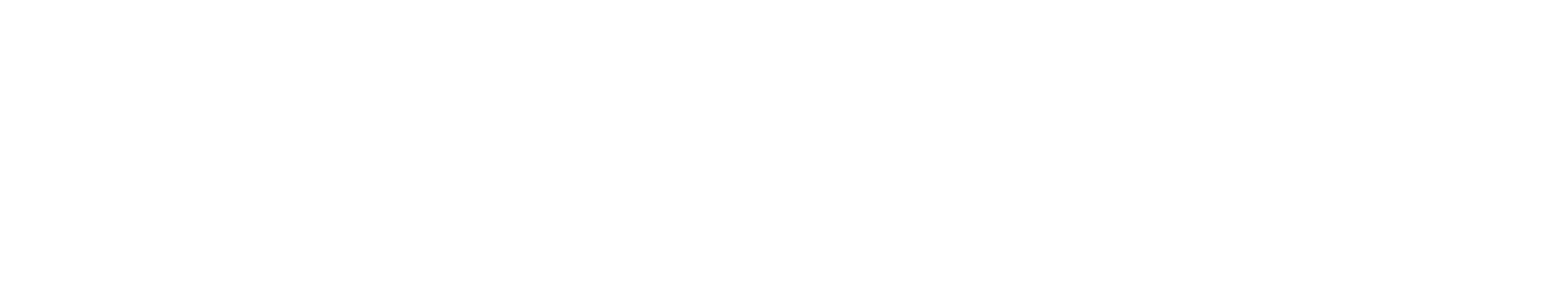

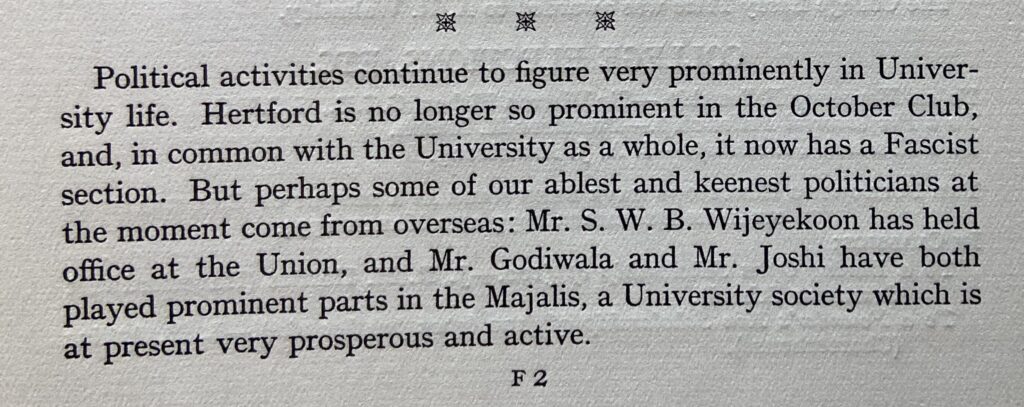

In the years afterwards, faced with both the Great Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe, many left-wing Oxford students would turn towards Communism — represented in Oxford by the October Club. Hertford College played a key role in the growth of the October Club and many of its early leaders were Hertford students. This story is told through the collection of surveys completed by dozens of alumni in the 1980s. The collection, uncatalogued until recently, presents a vivid and unseen picture of student life at Hertford from the 1920s through to the 1970s, but the richest and most fascinating collection of accounts is from the 1930s.

In the weeks following the general election, the October Club was founded at the end of Michaelmas term 1931. The founding President was Frank Meyer, a student at Balliol who was described in a report to the security services as “an unpleasant American of great drive and ability,” but many other members of the executive were Hertford students. Hertford student James Phelips wrote that “the founding Chairman, Secretary and Librarian of the October Club were all Hertford men.” Michael Rathbone wrote that he helped found the “avowedly Communist” October Club amidst his “disgust” at the 1931 election along with fellow Hertford students Tom Fox and Dick Freeman.

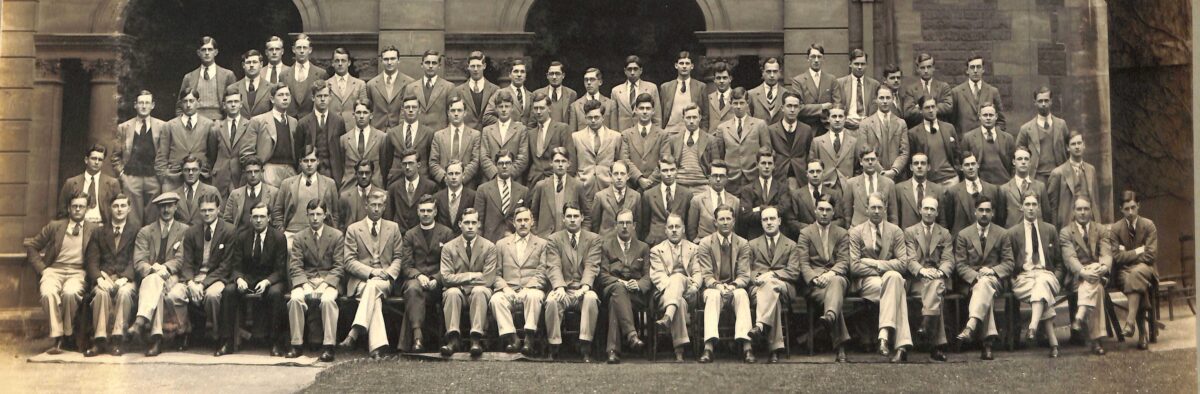

Dick Freeman, born in October 1910, went to Charterhouse before arriving at Hertford in 1929 as one of the more distinctive characters of the decade. He was a boxer and visited the Soviet Union in summer 1931 for four months, where he told his classmates he drove “tractors on a collective farm.” He returned from this trip, according to Hertford history student Hugh Elliott, “a convinced Communist” and was a key founder of the October Club. He was disillusioned with the Labour Club as it was “not left” or “not red” enough. Freeman also, according to classmate John Turner, had a dog named Mike who followed him everywhere.

Oxford was not initially hit by the Great Depression, with Christopher Gowan, a history student at Hertford, writing that undergraduates were not impacted by the New York Stock Market crash and, as late as 1932, they were “curiously unaffected” by the Great Depression. Engineering student Robert Jackson recalled simply that “Collapse of financial institutions in 1929 did not effect me.” Yet as the 1930s continued, Oxford began to feel the Depression more. DF Karaka, a student at Lincoln, wrote in a book published in 1933 that “extravagant waste has therefore diminished to the point of disappearance.” Meals and life got cheaper and simpler. Freeman pointed out in an essay published in 1934 that while Oxford “in the past [had] given the impression of bodies impervious to external events and the stress of economic factors,” undergraduates were now genuinely fearful of being unemployed upon graduation. With the Great Depression ravaging the globe, it was a time when, in the words of civil servant and Teddy Hall undergraduate Sir William Nield,“many people feared…that the ultimate crisis of capitalism was upon us.” This personal fear, combined with disillusionment with the National Government, began to push many students towards the October Club.

The meetings were held in a gym off the High Street and, by December 1932, the October Club had 300 members. The October Club was an unambiguously Communist club – they marched and studied Marx and Lenin. Freeman, who had become the Club’s president, organised an anti-war march on armistice day 1932 that required negotiations with the Proctors. However, one reason for their large support was a non-ideological one — the October Club had great guest speakers such as George Bernard Shaw and HG Wells, who was “merciless heckled.” Rathbone wrote that the great guest speakers “enticed membership” and drew in many non-Communist students. Meyer added, in his security service debriefing after becoming an anti-Communist, that “many [members] were simply interested in speakers and discussions” and held memberships in the Labour and Conservative clubs in addition to the October Club. Phelips wrote that Hertford was not actually that left-wing a college – Hertford’s leading role in the October Club was mainly due to friends recruiting their friends. Despite the heightened ideological climate, many friendships continued unaffected. JMD Kerr, a member of the University Air Squadron, roomed with an October Club executive at Hertford and observed that “apart from a little good humour badinage at breakfast these things were never allowed to interfere with our day to day relationship.”

One of the other key events in the history of the October Club was the Hunger Marches in autumn 1932. Dick Freeman described the marchers, a protest of unemployed men from Lancashire heading to London, in an essay written two years later:

“Those who saw the Marchers come into Oxford on a cold winter afternoon, many with sufficient clothing to keep them properly warm even when marching, and most with their feet tied up in caricatures of boots, will not forget the realization that these men were engaged in a fight, a bitter fight for reasonable living conditions. It would have been unnatural if many young men who had never thought of the question in terms of living, under-fed, badly clothed workers, had not made an emotional comparison between their own position and that of the marchers”.

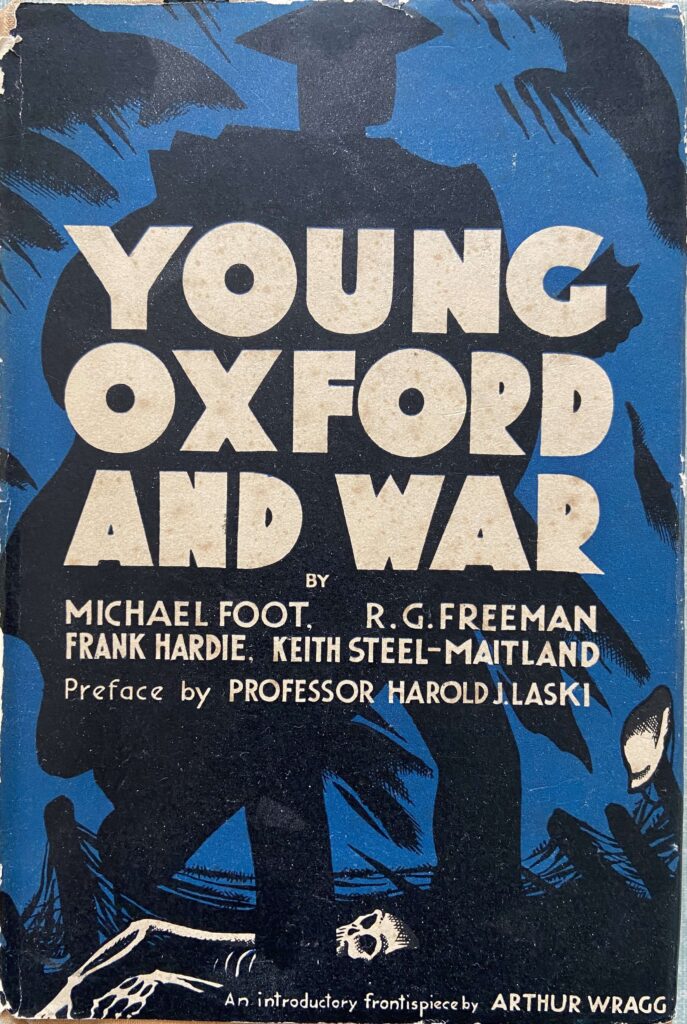

Dick Freeman, in his essay for ‘Young Oxford and War’, published in 1934

Hertford history student Brian Matthews helped to receive them as they arrived at a rainy Gloucester Green and “serve them with hot drinks and soup and blankets.” Hertford students James Phelips, Vincent Giardelli and others served them dinner in the Drill Hall where they stayed in Oxford and provided “food, clothes, encouragement and physical protection against Fascists from London.” Hugh Elliott was also at the Drill Hall and remembered seeing their head wounds from clashes with police — this sight of the “suffering of the unemployed” is what drove him to the October Club. Despite violating the rules of the proctors, some students marched with them down High Street the next day as they left Oxford and crossed Magdalen Bridge. Both the Labour Club and the October Club played a role in welcoming the Hunger Marches — Hertford student Charles Moore attended some of the hunger marches meetings and described them as “very Communist and rather dangerous” — but the balance of the help depends on whether accounts were written by members of the Labour or October Clubs.

Despite this rapid growth, it did not last. The October Club’s momentum was sharply blunted soon after its founding. This was in part because of the organisational work of a Canadian Rhodes Scholar at Lincoln — David Lewis, later leader of the New Democratic Party of Canada. Lewis played a key role in the Labour Club and his biographer described him as the “barrier against which the Communist wave broke.” A fellow student described him as “absolutely devastating” in debates against the October Club spokesman, adding that “I cannot recall a single individual of any intellectual stature, like David, who spoke for the October Club. They were weak.”

Other students had their own reasons for turning against Communism. Michael Rathbone did not give a reason, but he was back with the Labour Club and warning against the October Club by 1934. Ronald Vearncombe recorded he was:

“appalled and sickened by the deliberated distortions, the lip-service to, and the contempt for, democratic processes, and the subservience of moral principles to a dogma as insensitive and monstrous as fascism itself. What difference did it really make whether a black tide or red tide threatened to engulf us.”

Hugh Elliott eventually became disillusioned with the October Club due to leadership struggles, differences of opinion with hard-line Communists, and the October Club’s “encouragement of ‘free sex’ and the resulting mess in the lives of my friends.” He soon left the club.

The October Club was suspended by the University in 1933 — Freeman described the Proctors as determined to prevent Oxford “becoming the battle ground between Communists and Fascists.” Freeman claimed that the other political clubs failed to stand with the October Club but Michael Foot, a Liberal at the time and later the leader of the Labour Party, described Freeman’s version of events as “inaccurate and misleading.” The October and Labour Clubs gradually became better at cooperating by Trinity Term 1933 and merged in 1935 either out of a popular front or infiltration strategy depending on who you ask.

Some Oxford Communists later disavowed the party. On the other hand, Freeman remained a member of the Communist Party, engaging in street battles against Oswald’s Mosley’s Fascists and serving in Italy during the war, until he resigned from the Party in the early 60s and was appointed as a Circuit Judge. Students turned to the October Club because, amidst the crisis, they lost faith in democracy. Despite the Soviet famines and purges in the 1930s, it seemed like the best path forward for many in Oxford. Democratic failure allows extremism to flourish. Democracy would soon be put to an even greater test with the coming of the Second World War.

All images are of items in Hertford College Archives unless otherwise credited. For more information about this collection, please go to the Featured Collections in our online catalogue. Watch out for further blogs exploring these fascinating memoirs.